Blind Sided: A Reconceptualization of the Role of Emerging Technologies in Shaping Information Operations in the Gray Zone

Authors: Ashley Mattheis, Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, Varsha Koduvayur, Cody Wilson

Table of Contents

- Toward a New Understanding of Information Propagation and Mobilization

- What Is Gray Zone Competition?

- The Gray Zone Information Context

- Methodology: Applying Evolutionary Theory to Gray Zone Information Operations

- Propagation of Perspective

- Information Operations Methods in the New Media Sphere

- 6.1 Crosscutting Informational Modalities

- 6.2 Localized and Platform-Specific Methods

- Affordance Manipulation

- 6.3 Evasive and Subversive Methods

- Identity Masking and Anonymity

- Avoiding Detection and Subverting Regulation/Terms of Service

- 6.4 Scalar and Multi-Platform Methods

- Algorithmic Manipulation

- Case Study: Daesh’s Use of Social Media and Subsequent Deplatforming

- 6.5 Multi-Platform IO Methods

- Hashtag Hijacking

- Influencer Marketing (Lifestyle Branding and 360 Degree Marketing)

- Political Astroturfing

- 6.6 State and Pseudo-State IO Campaigns

- Domestically Targeted State and Pseudo-State Campaigns

- State-Specific Campaigns

- Amplification and Automation Through Bots

- Mobilization Repertoires

- Implications

Glossary

affordances: In the new media sphere context, affordances are sets of features specific to particular software or platforms. Users often utilize these features in ways that developers did not plan.

bots: Short for robots, bots are automated programs that perform repetitive tasks and can be designed to mimic the online activity of humans.

disinformation: Media that contains false or misleading information that is created and shared to intentionallyharm a specific target.

gamification: The process of adding “game” elements, such as leaderboards and rewards systems, to non-game environments.

gray zone competition: The gray zone is the space between war and peace. Gray zone competition can be thought of as competition between actors (state or non-state) that exceeds normal peacetime competition but does not meet the threshold of a declared war.

hashtag hijacking: Using an existing popular hashtag to circulate unrelated content.

information environment: The full spectrum of actors and systems that share and use information.

information operations (IOs): Information operations use information to target an audience with a specific message to create a desired change within that audience.

malinformation: Information that is based on truth but is exaggerated or otherwise taken out of context to cause harm.

meme: A term describing how small bits of cultural information are passed between people, replicated over and over, and spread widely.

memeification: The process of turning a piece of content (e.g., taglines, images, song snippets, cultural icons) into a meme.

misinformation: Media that contains false or misleading information but that is not intentionally shared to cause harm. Often the sharer is unaware that the media contains false or misleading information.

new media ecosystem: Traditional, digital, and social media in an interrelated ecosystem that allows participants to be sources, producers, and consumers of information, often simultaneously.

polluted information: A catch-all term for disinformation, misinformation, and malinformation.

sockpuppet accounts: Fake social media accounts that are meant to appear real to other users.

Introduction

In June 2022, Facebook and Twitter accounts suddenly focused their wrath on Australian company Lynas. The previous year, Lynas—the largest rare earths mining and processing company outside China—had inked a deal with the U.S. Department of Defense to build a processing facility for rare earth elements in Texas. Over a year after the deal was signed, concerned Texas residents began taking to social media to loudly voice opposition to the deal. They claimed the facility would create pollution and toxic waste, endangering the local population. Residents disparaged Lynas’s environmental record, and called for protests against the construction of the processing facility and a boycott of the company.

Only these posts weren’t coming from Texas residents at all. The lead voices on the topic weren’t even real identities. The campaign was led by fake accounts set up and maintained by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in an information operation (IO) aimed at smearing the image of China’s competitors in the field of rare earths—metals critical to producing advanced electronics, electric vehicles, batteries, and renewable energy systems. China is a behemoth in this field, controlling over 80% of global production of rare earths, and is eager to maintain its supply chain dominance.[i]

This PRC-led campaign against a rival in the rare earths field was discovered by cybersecurity firm Mandiant, which has also unearthed past PRC-led IOs aimed at promoting “narratives in support of the political interests of” Beijing.[ii] Nor was Lynas the only company that China targeted in its attempts to use the information space to ensure continued rare earths dominance. In June 2022, the same PRC-led campaign targeted both Appia Rare Earths & Uranium Corporation, a Canadian rare earths mining company, and the American rare earths manufacturer USA Rare Earth. Both companies were bombarded by “negative messaging in response to potential or planned rare earths production activities,” Mandiant noted.[iii]

China’s desired end was to damage Western companies in the rare earths sector to thwart would-be competitors. In doing so, Beijing seeded a social media operation, using accounts carefully crafted to look like Texas residents voicing very real fears about the damage Lynas could do to their communities.

China’s information operations—and, indeed, information operations in general—are not a new phenomenon. But IOs have metamorphosed and become turbocharged in today’s digital information environment. As Thomas Rid has observed, such operations have been “reborn and reshaped by new technologies and internet culture.”[iv] Characteristics of the digital-age information environment allow various actors to leverage information operations to propagate information and mobilize audiences for their own ends (or alternatively, to suppress the spread of information or mobilization of populations, as we will discuss).

This dynamic has a deep influence on how information operations are conducted in the gray zone, which is the space that exists between war and peace. Gray zone competition can be thought of as competition between actors (state or non-state) that exceeds normal peacetime competition but does not meet the threshold of a declared war. The “gray zone” is synonymous with irregular warfare. Modern information operations are favored by gray zone actors because they allow competition with adversaries without direct physical confrontation. To carry out gray zone information operations, actors rely on and exploit psychological biases, social and political structures, characteristics and affordances of the media and information environments, and emerging technologies. Further enabling gray zone information operations is the new media ecosystem, which comprises traditional, digital, and social media in an interrelated ecosystem that allows participants to be sources, producers, and consumers of information, often simultaneously.

This report uses the framing of ends, ways, and means to analyze the impact of information operations.[v] By ends, we refer to the end state or outcome that information operations actors are seeking to achieve—in other words, why the actor is conducting the IO in the first place. Ultimately, all information operations have a desired end, be it political, economic, diplomatic, or social. By ways, we refer to how actors seek to achieve their preferred end through information operations (including by amplifying or suppressing information). And by means, we refer to the specific information operation that the IO actor employs—in other words, the specific “play” that they select from the IO playbook that this report presents. IO actors have a number of tools at their disposal to conduct the IO, which provide the methods, capabilities, and resources for conducting information operations.

Policymakers and security professionals in liberal democracies have repeatedly been blindsided by emerging gray zone IO threats, while their focus has been on past IOs they have encountered. This report’s ambitious goal is to take a significant step toward changing this dynamic by de-centering the prevailing analytic focus on the actors employing information operations. Instead, the report focuses on the strategies and tools that actors employ in their information operations to achieve their desired end state. When analysts are overly focused on the activities of a particular actor, they open themselves up to being blindsided. After all, in this information environment, no actor formulates its IOs in a vacuum. For example, when a left-wing movement successfully mobilizes large numbers of people to the streets in protest, its success is studied not only by that movement’s adherents, but also by white supremacists, pro-democracy social movements in the Middle East, authoritarian states seeking to exacerbate social divisions in the West, jihadist groups, and other actors. Successful IOs and strategies are replicated not only by the actor that pioneered them and by its allies, but also by a multiplicity of other actors with various ideologies, motivations, and goals.

The report makes three primary contributions. First, it offers the propagation-mobilization framework for understanding IOs in the gray zone. This framework holds that there are two ways IOs are used in gray zone strategies—propagation of information and mobilization to action—to achieve a desired end. Gray zone IOs can be understood as having one of two impacts on these lines of effort, creating either positive or negative feedbacks that amplify or suppress propagation and mobilization to action. Though this framework may appear at first blush to be a simplifying schema, we believe it in fact has revolutionary implications, as this report details later. Second, this report adapts evolutionary theory to enhance our analytic understanding of information operations in the gray zone. Evolutionary theory has previously been employed in certain contexts in the social sciences, but we assess it as uniquely valuable for illuminating information operations.

Third, this report outlines a robust range of digital and offline IOs, explicates their utility for a variety of actors, and maps their interactive potential. It provides a “playbook” for understanding information operations as a critical means to gray zone competition. In doing so, we seek to create understanding of how gray zone actors employ information operations. The impact of such an elucidation may at first seem simple, but we believe that it will have a potentially profound effect. In pulling together various and seemingly disparate IOs into one binding framework, we hope to provide a richer understanding of IOs than that conveyed by actor-focused analyses, which will potentially overlook the evolutionary nature of IOs and thus possibly miss emergent IO threats.

Our endeavor here is similar to that undertaken by the iconic chess theorist Aron Nimzowitsch, whose 1925 volume My System worked to discern principles and hence a framework for understanding the complex war being fought on the 64 squares of the chessboard. As Nimzowitsch detailed:

The individual items, especially in the first part of the book, are seemingly very simple—but that is precisely what is meritorious about them. Having reduced the chaos to a certain number of rules involving inter-connected causal relations, that is just what I think I may be proud of. How simple the five special cases in the play on the seventh and eighth ranks sound, but how difficult they were to educe from the chaos! Or the open files and even the pawn chain! …. I now hand this first installment over for publication. I do so in good conscience. My book will have its defects—I was unable to illuminate all the corners of chess strategy—but I flatter myself of having written the first real textbook of chess and not merely of the openings.[vi]

We believe we are, in a similar fashion, creating a playbook for understanding information operations in the gray zone. Our aim is to provide a clear framework in which IOs can be understood and—more importantly—predicted, by concretely discerning the IO strategies and tactics that actors may deploy, and noting their interlinkages and evolutions. While no such summary can be exhaustive of all potential IOs, particularly given the ever-changing technological context and the creative capacity of gray zone actors, the depth of this summary offers an essential overview of the utilities, modalities, and capacities embedded in contemporary gray zone IO competition.

To provide a roadmap of this report, after describing the modern information environment and its role in enabling gray zone IOs, we lay out our framework in full. Drawing on the work of Canadian scholar Yannick Veilleux-Lepage, who recently published a book applying evolutionary theory to airplane hijackings, we similarly apply evolutionary theory to information operations.[vii] This report also divides IOs into the two distinct lines of effort (LOEs) of propagation and mobilization. Propagation and mobilization LOEs can operate independently or feed into one another, producing feedback loops. The outcome of both propagation and mobilization can be either amplifying or suppressive. The desired outcome shapes which IOs will be selected for a particular LOE.

Amplifying propagation is rather intuitive: doing so is intended to rapidly spread information through the new media ecosystem. By contrast, suppressive propagation is the silencing of information in the new media ecosystem, which can come from account takedowns, censorship (including producing an environment of self-censorship), harassment, or other means of preventing information from spreading. Similarly, amplifying mobilization is one of the classic goals of IOs, to make a target population go out and do something, such as donating blood, voting, protesting, carrying out terrorist attacks, or storming the U.S. Capitol. Suppressive mobilization aims to prevent people from doing something, such as staying home instead of voting, refraining from going to ISIS’s caliphate, declining to join a gang, or declining to take a COVID-19 vaccine.[viii]

Using this report’s framework, we discuss the varieties of propagation and mobilization IOs, how these IOs are adapted across technology platforms and by users, and how these IOs are transmitted to other actors. This allows for a better understanding of how some IOs predominate while others die off. Our framework also allows for analysis of “selection factors,” which can be broken down into the categories of feasibility, legitimacy, and effectiveness. Feasibility is a selection factor that considers how readily a particular IO can be carried out within a particular context; legitimacy gauges how well the information or mobilization strategies resonate with the target audience; and effectiveness measures whether the propagation or mobilization lines of effort have the intended effect.

The propagation-mobilization framework also has other implications. While mobilization is generally well defined in the literature, propagation’s role is an important departure from analysis of IOs that focuses on “fake news,” including disinformation. In place of such concepts, this report uses propagation of perspective as a value-neutral term to describe information intended to shape an audience’s perspective. The propagation of perspective is a socio-technical process that utilizes information and cultural relations to achieve strategic goals. We may see these goals as noble or malign; but we should understand that a variety of actors with differing and often directly conflicting goals are watching and learning from one another. They are, often unintentionally, sharing IOs. Unlike the concepts of fake news or disinformation, propagation of perspective recognizes the complexity of the new media ecosystem and the myriad ways that information travels in that ecosystem. The socio-technical processes that enable propagation of perspective draw upon interactivity, convergence, and access to vast quantities of data to circulate information through the media ecosystem.

To highlight how this works, we examine the debate surrounding the origins of COVID-19 to showcase how information is propagated through the new media ecosystem, including how certain theories about COVID-19’s origins were amplified while others were suppressed. The complex and multifaceted nature of how perspective propagates is on full display as we describe the ways in which legitimate information and perspective were ensnared in purges of conspiracy theories.

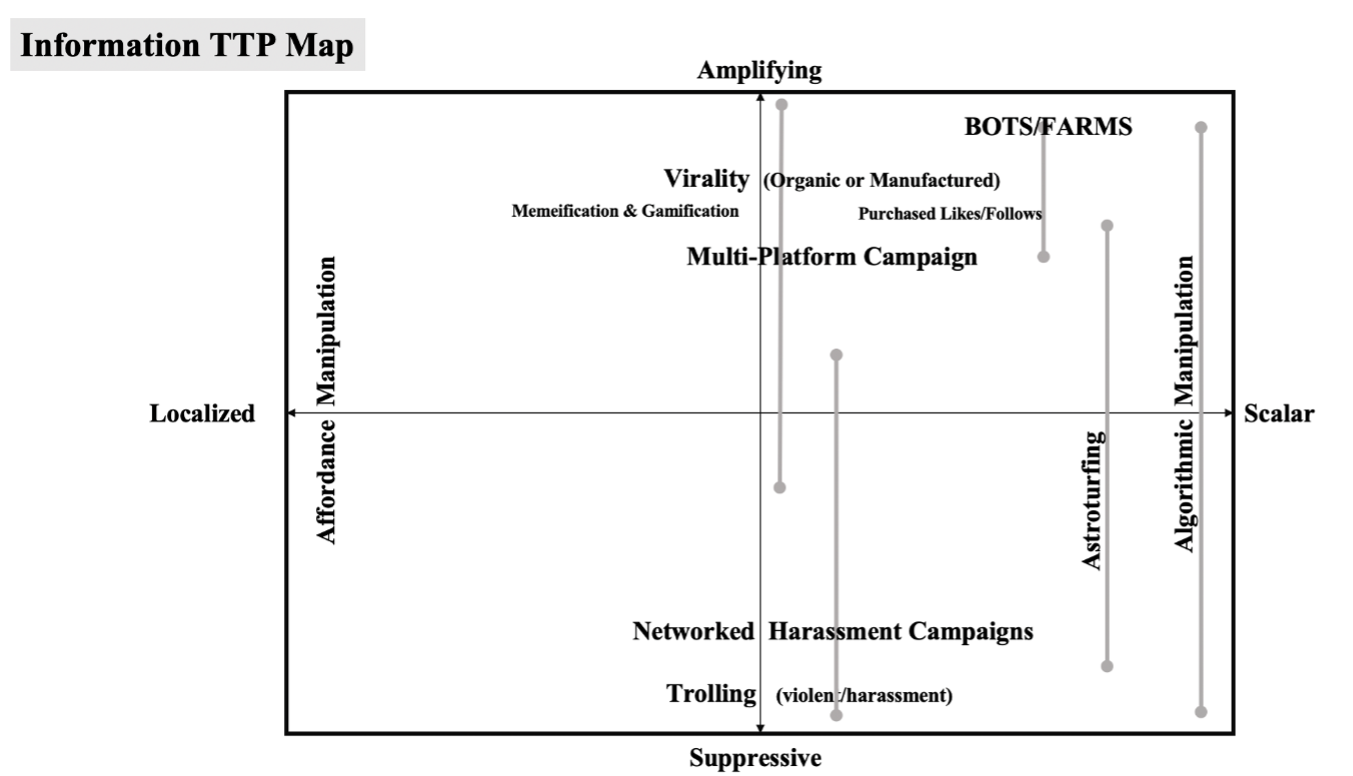

By applying the propagation-mobilization framework to gray zone IOs, we examine new media IOs that manipulate communication technologies like digital and social media to propagate information rapidly to a potentially enormous audience. Such manipulation can be achieved in localized operations or at scale. Localized IOs include affordance manipulation and evasive tactics. Scalar IOs include multi-platform operations and algorithmic manipulation.

The propagation-mobilization framework also allows us to examine how IOs can mobilize a target audience. Mobilization repertoires include online actions related to the interactivity of digital and social media, including circulation-based IOs such as interactive circulation, intermediation, and reactive circulation, as well as suppressive IOs like doxxing, networked swarms, brigading, and swatting. Mobilization repertoires also include offline actions such as non-violent protests, movements, and events, and also violent versions of each. Importantly, these action IOs, both online and offline, have been developed in large part by everyday people rather than by professionals trained to deploy information operations.

These mobilization IOs become exploitable by gray zone actors precisely because they are responses and actions that people already consider appropriate in the context of socio-political engagement. Gray zone IOs may thus lead to what appears to be grassroots mobilization that has in fact been manipulated by outside actors, a practice known as astroturfing. The campaign against Lynas introduced at the beginning of this report is an example of astroturfing. Moreover, threat actors may try to coopt existing movements or manipulate their mobilization.

Gray zone IOs are likely to increase in frequency, scope, and sophistication. With further technological innovation, IOs will likely become tougher to detect. Moreover, technological and social developments have rendered a state’s population more vulnerable to targeting by IO actors than in years past. As we will show in this report, the new media ecosystem has also drastically shrunk the time between propagation of information and mobilization to action—a shrinkage that IO actors will seek to exploit. The time for states and societies to build resilience to gray zone IOs is now.

Hostile actors’ IOs represent a serious threat to democracy. Such IOs seek to fray the fabric of trust and tolerance that binds states, societies, communities, and institutions together. Hostile actors are able to do so for a relatively low cost. Thus, we view this report’s admittedly ambitious goals with some urgency.

1. Toward a New Understanding of Information Propagation and Mobilization

At the center of this report is a new framework for understanding gray zone IOs, the propagation-mobilization framework. Though the contours of the propagation-mobilization framework may seem simple, we believe its implications are profound. The framework holds that there are two lines of effort to gray zones operations: propagation (e.g., of communications, ideas, conspiracy theories, memes) and mobilization. Gray zone IOs, whether employed by adversaries or allies, can be understood as having one of two impacts on these lines of effort, creating positive feedbacks (amplifying effects) or negative feedbacks (suppressive effects). Not every gray zone IO has an impact on both propagation and mobilization, but gray zone IOs increasingly operate on both lines of effort simultaneously.

In this report, we examine how IOs are employed in gray zone competition to advance propagation and mobilization. In doing so, we employ an evolutionary framework that focuses on the IOs employed rather than on the actors employing them. The evolutionary framework has great explanatory potential in the social sciences, and for disinformation specifically. Coupled with this report’s propagation-mobilization framework, evolutionary theory can illuminate the kind of IOs we will confront in the future.

The first benefit of the propagation-mobilization framework is that it avoids the information-disinformation binary that often dominates these discussions. We do not seek to avoid this binary because we possess a postmodern skepticism of truth. Rather, there are three reasons we believe the information-disinformation binary can be unhelpful to analyzing gray zone IOs. First, IOs can be significant even if they are true, and indeed, gray zone IOs have long included elements of truth. This can be said, for example, about the IOs historically employed by the United States. Analyzing the Central Intelligence Agency’s information operations in the immediate wake of World War II, Thomas Rid notes that they employed a “blend of covert truthful revelations, forgeries, and outright subversion.”[ix] Second, even if an IO is true, it can at the same time be misleading. Disproportionate attention provided to certain factual incidents—for example, overemphasis on crimes committed by certain ethnic groups, or on adverse effects of certain vaccines—can conjure in the audience a feeling of ominous trends that may not reflect reality. And third, focusing solely on disinformation means that one will miss relevant evolutionary IOs that, while unrelated to disinformation in themselves, are highly relevant to the future of disinformation propagation. In other words, IOs are not unidirectional: disinformation actors do not simply learn from and copy other nefarious actors. Rather, IOs generated by “legitimate” actors may be coopted and evolved by nefarious ones. Anyone studying disinformation solely through the lens of disinformation-related IOs risks becoming blindsided to the evolutionary potential of non-disinformation IOs to be used by disinformation actors.

Another important reason to avoid the information-disinformation binary is truth decay in the mainstream media environment. Often the lines between information and disinformation are too brightly drawn by observers. Truth decay is determined by multiple factors in the information sphere, including the rush to publish, the push toward simplified clickbait, societal polarization (which increasingly extends also to journalists), and a social media environment in which the popularity of our every thought or viewpoint is immediately known. Mainstream media is often perceived as taking sides in cultural conflicts rather than representing objective truth. A vulnerability to adversary IOs exists when an audience perceives that those IOs better reflect the reality it experiences than does the mainstream information sphere. If the mainstream information sphere loses credibility, it will lack counter-propagation power.

A second benefit of the propagation-mobilization framework is that, through its emphasis on tactics over actors, the framework will help to avoid strategic surprise. Current frameworks tend to be actor-centric, a dynamic that can produce blind spots. For example, the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol surprised authorities, but should have been more foreseeable. Multiple mobilizations occurred from 2020-21 in the United States. In sequential order, the most important mass mobilizations during the period prior to the “stolen election” mobilization were: 1) anti-lockdown protests, 2) a pro-racial justice mobilization, and 3) a separate mobilization by militant anti-fascist and anarchist activists, particularly in the Pacific Northwest. The tactics employed on January 6 were not foreseeable through a framework focused narrowly on actors who mobilized around the notion of a stolen election, but the likelihood of those events could be discerned by examining strategic evolutions across all four of these mobilizations. For example, the mobilization strategies of massing to overwhelm authorities and shutting down buildings symbolic of political power could be discerned in all three of the previous mobilizations. Future mobilizations leveraged to subvert democratic systems can be better predicted and prevented through this report’s framework.

A third benefit we foresee from this report’s framework is that it can enable more precise identification not just of adversaries’ use of emerging technologies in the gray zone but also the relevant signs that certain IOs are growing in significance. For example, several small-scale but relatively violent protests directly preceded the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. These were conducted by groups such as the Proud Boys, which leveraged the notion of a stolen election to amplify, promote, and direct violence in these small-scale “seed” events, which showcased mobilization features from the previous three 2020 mobilizations. In particular, they showcased the shift to street violence during the evening (dark) hours of the protests, skirmishes by the more aggressive participants, and vandalism of perceived opponents’ property. This highlights how groups’ tendencies to replicate selected (useful) strategies across disparate mobilizations provides a road map for prevention and response planning. Thus, this report’s framework can empower democratic actors to select strategies and corresponding IOs that will yield the greatest return on investment over time.

The fourth benefit relates to strategic deployment of complementary capabilities. The propagation-mobilization framework allows for clearer categorization of the strategic purpose of various emerging technologies in the gray zone. Its categorization of gray zone IOs into those that will have positive or negative feedbacks on propagation and mobilization can enable the development of comprehensive strategies where each capability supports all other elements.

With the advantages we discern from this framework in mind, we now outline how the propagation and mobilization elements of gray zone IOs came to be more tightly wound with one another than ever before.

The Technological Change: The World of the Social Web. In the information sphere, technology has allowed ever greater dissemination of information and messaging. Recent developments in the digital sphere are no less seismic than was Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press. Indeed, the internet itself has undergone two different revolutions in the past three decades.

The internet as it exists today is a far cry from where it stood in the 1990s. The first iteration of the internet, Web 1.0—the “read-only” internet—was characterized by static webpages that could be read but offered little to no interactivity. Around the turn of the century, Web 2.0, or the “read-write” web, emerged. This iteration allowed users to create blogs, post multimedia content (e.g., audio recordings or videos), and engage more easily with content on webpages. Web 2.0 offered greater interactivity but did not change the average internet user into a content producer. The social web turned this dynamic on its head. On sites in the social web (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, YouTube), users were no longer primarily consumers of someone else’s material but were put in the position of being content producers themselves.[x]

Alongside the web’s evolution, internet adoption grew globally, as did adoption of social media in particular. For example, Facebook had 608 million monthly users at the end of 2010. By the end of 2014, that number had soared to nearly 1.4 billion, and it has by now reached nearly 3 billion.[xi] Thomas Rid notes how the changed technological environment transformed information operations. After tracing three preceding waves of disinformation, Rid writes that “the fourth wave of disinformation slowly built and crested in the mid-2010s…. The old art of slow-moving, highly skilled, close-range, labor-intensive psychological influence had turned high-tempo, low-skilled, remote, and disjointed.”[xii] It is this quick tempo of IOs empowered by technological changes that erodes the distinction between propagation and mobilization in the IO sphere. We illustrate this through the “virtual plotter” model employed by Daesh (also known as the Islamic State or ISIS), which represented a successful gray zone IO technique by a non-state actor.

Daesh and the Virtual Plotter Model. Though it is difficult to measure, most experts believe that radicalization to violent extremism is occurring faster than ever before (e.g., the time between an individual beginning to explore violent extremist ideas or identities and acting on their behalf is compressed). Social media, with its frenetic pace of communications and the social bonds it fosters, can create an environment where extremist groups more quickly influence people’s identity formation in an extremist direction and drive them to action. Put differently, the distinction between propagation of, and mobilization in service of, violent extremist ideas has become less pronounced. Daesh’s online activities demonstrate this.

In addition to using social media to help mobilize record numbers of foreign fighters to Syria during the country’s civil war, Daesh engineered a process by which its operatives could directly guide lone attackers, playing an intimate role in the conceptualization, target selection, timing, and execution of attacks. Essentially, operatives in Daesh’s external operations division coordinated attacks online with supporters across the globe, most of whom never personally met the Daesh operatives they conspired with. Virtual plotters thus could offer operatives the same services once provided by physical networks. The model helped transform lone attackers who relied heavily on the internet from the bungling wannabes they once were into something more dangerous.[xiii] Further, the virtual plotter model created a process whereby propagation and mobilization occurred through the same mechanism. This stood in stark contrast with earlier jihadist propaganda, which would put out calls for violence and hope that these calls would be followed without the groups having any real way of ensuring that people would take up their calls for action.

The experience of the first Daesh virtual plotter to gain international recognition, British hacker-turned-terrorist Junaid Hussain, illustrates how this model wed propagation to mobilization:

May 2015

- Hussain encouraged Elton Simpson and Nadir Soofi to attack the “Jihad Watch Muhammad Art Exhibit and Cartoon Contest” held in Garland, Texas. Simpson and Soofi arrived at the venue and opened fire but were quickly killed by an alert security officer.[xiv]

- Hussain was in contact with Munir Abdulkader, a 22-year-old from West Chester, Ohio. He encouraged Abdulkader to launch an attack against U.S. military and law enforcement personnel. Authorities arrested Abdulkader after he purchased an AK-47 to further this plot.[xv]

- A 17-year-old with links to Hussain was arrested in Melbourne, Australia for plotting a Mother’s Day massacre. Hussain provided the teen with bombmaking instructions and encouraged him to launch an attack in Melbourne.[xvi]

June 2015

- Hussain communicated with Usaamah Abdullah Rahim, a Daesh sympathizer who was killed while attacking a police officer and FBI agent in Roslindale, Massachusetts. An investigation following the attack revealed that Hussain initially encouraged Rahim and two co-conspirators to attack Pamela Geller, who had organized the Garland art contest.[xvii]

- Justin Nojan Sullivan, a 19-year old from Morganton, North Carolina, conspired with Hussain to plan a mass shooting that would be claimed in Daesh’s name. Sullivan was caught by the FBI before he could carry out the attack. But in the weeks before the attack, Sullivan succeeded in murdering a neighbor.[xviii]

- Hussain communicated with Fareed Mumuni and Munther Omar Saleh, members of a small Daesh cell in New York and New Jersey. Hussain encouraged Saleh to conduct a suicide bombing against law enforcement officers, and Mumuni stabbed an FBI agent who was executing a search warrant at his residence.[xix]

- Hussain recruited Ardit Ferizi, a Daesh sympathizer living in Malaysia, to hack into the server for an Illinois company and release personally identifiable information on around 1,300 U.S. military or government personnel who had shopped there. Daesh subsequently released this information on Twitter as a list of targets for militants in the United States.[xx]

July 2015

- Hussain conspired with Junead Khan, who intended to attack U.S. military personnel in Britain. Hussain gave Khan bombmaking instructions and tactical suggestions. Khan was arrested prior to carrying out his attack.[xxi]

August 2015

- Zunaid Hussain, a doorman in Birmingham (U.K.), planned to detonate a bomb along the tracks of a rail line between Birmingham and London. Hussain reportedly communicated with Junaid Hussain over Twitter and Kik, another messaging platform.

Other examples of how the virtual plotter model wedded propagation to mobilization abound. Rachid Kassim, a French social worker turned jihadist, travelled to Syria to join Daesh in 2015. Like Junaid Hussain, he established a noteworthy social media presence, using his ability to speak both French and Arabic to connect with aspiring jihadists in his home country.[xxii] Kassim ran a popular Telegram channel, Sabre de Lumière (Sword of Light), in which he called for attacks in European countries and distributed “hit lists” of high-profile individuals.[xxiii] He also engaged one-on-one with aspiring operatives, assisting them in carrying out attacks. Prior to his death in a July 2017 U.S. airstrike, Kassim was involved in numerous plots, including the following:

June 2016

- French authorities believe Kassim was in contact with Larossi Abballa, a 25-year-old French jihadist who murdered a police captain and his partner in Magnanville, France.[xxiv] After slaying the couple, Abballa menaced their three-year-old child. He streamed this on Facebook Live, saying: “I don’t know yet what I’m going to do with him.”

July 2016

- Kassim was in contact via Telegram with Adel Kermiche and Abdel Malik Nabil Petitjean, who slit the throat of an elderly priest during services at a church in St. Ètienne-du-Rouvray. Authorities believe Kassim introduced the two operatives, who lived over 400 miles apart and first met in person shortly before the attack. Kassim took over Kermiche’s Telegram account after he was killed by police, one indication of his importance to the attackers.[xxv]

September 2016

- Kassim was in contact with a 15-year-old French boy who planned to carry out a knife attack in Paris.[xxvi]

October 2016

- Kassim was in contact with an 18-year-old who was arrested in Clichy-la-Garenne (Hauts-de-Seine) for plotting an attack.[xxvii]

- Kassim was in contact via Telegram with a young couple in Noisy-le-Sec who were planning an attack. Authorities arrested them after determining that their attack was imminent.[xxviii]

In addition to his role in these plots, Kassim succeeded in bringing disparate individuals together to form cells (as he seemingly did for the attackers in the aforementioned St. Ètienne-du-Rouvray church attack). In September 2016, French authorities arrested a group of female terrorists who tried to set off a car bomb near Paris’s Notre Dame Cathedral. One of them stabbed an officer outside the Boussy-Saint-Antoine rail station as authorities made the arrest.[xxix] Before the attempted attack, none of the women had had any type of relationship with one another. Instead, they were brought together solely by Kassim. In connecting the women, Kassim merged two different lines of terrorist effort in two different parts of France based on one operative’s reluctance to carry out a suicide operation. Sarah Hervouët, a 23-year-old convert to Islam who was planning an attack in the southeastern French commune of Cogolin, had been communicating with Kassim over Telegram. Acting on Kassim’s orders, Hervouët drafted her will, wrote farewell letters to relatives, and made a video proclaiming her allegiance to Daesh. But she lost her appetite for this “suicide-by-police” attack. So Kassim connected her with two other women preparing to carry out an attack in Paris instead.[xxx] Though the women failed to carry out the dramatic attack that Kassim hoped for, the Notre Dame case demonstrates the speed, agility, and adaptability of the virtual plotter model, and how it weds propagation to mobilization.

Pairing propagation and mobilization is even easier when, unlike in Daesh’s virtual plotter model, the IO is not attempting to mobilize the target to do something illegal, in which case the possibility of legal penalties may serve as a deterrent. In recent years, adversarial IOs targeting the United States and Canada have tried to mobilize the target audience in multiple ways, including mobilizing to activities that are both legal (e.g., protests) and illegal (e.g., carrying out attacks, looting).

2. What Is Gray Zone Competition?

“This is another type of war, new in its intensity, ancient in its origin — war by guerrillas, subversives, insurgents, assassins, war by ambush instead of by combat; by infiltration, instead of aggression, seeking victory by eroding and exhausting the enemy instead of engaging him.” -– John F. Kennedy

The concepts of peace and war typically connote a binary condition—a white or black distinction. However, in the twenty-first century, interstate conflict is more likely to take the form of gray zone competition rather than outright war. The gray zone is the space between peace and major armed conflict or war. As its name implies, there can be multiple shades of gray. The gray zone is thus a spectrum between the two polar opposites, with the peaceful or diplomatic competition between states at one end of the spectrum and open, violent conflict between states at the other end. Many historical events since the end of World War II can be understood as residing along this spectrum, in the form of interstate competition that does not meet the threshold of open warfare. Such events can be termed gray zone competition. Gray zone competition can be seen in clandestine activities like intelligence collection, covert operations, and information operations). IOs, sometimes also called information warfare, refer to “the strategic use of technological, operational, and psychological resources to disrupt the enemy’s informational capacities and protect friendly forces.”[xxxi] Such operations have been highly effective gray zone tools.

2.1 Introduction to the Gray Zone Environment

The gray zone presents significant security challenges for states, as activities in the gray zone can be hard to detect, define, and attribute. States must define for themselves what meets the threshold for an act of war. Competitors try to undermine a state’s interests while staying below this threshold. Complicating matters further, the gray zone is notoriously difficult to define.

The gray zone is not a new space. Irregular warfare, low-intensity conflict, and asymmetric warfare have all preceded coinage of the gray zone competition concept. As far back as 1962, President John F. Kennedy described one aspect of what would now be called the gray zone, saying: “This is another type of war, new in its intensity, ancient in its origin—war by guerrillas, subversives, insurgents, assassins, war by ambush instead of by combat; by infiltration, instead of aggression, seeking victory by eroding and exhausting the enemy instead of engaging him.”[xxxii]

The gray zone possesses several unique characteristics. As Philip Kapusta describes it, the gray zone is “characterized by ambiguity about the nature of the conflict, opacity of the parties involved, or uncertainty about the relevant policy and legal frameworks.”[xxxiii] The ambiguous nature of the gray zone creates challenges that do not exist in traditional decision-making models. The opacity of the gray zone allows both rival state actors and non-state actors to produce their own challenges to a state. Rival states and non-state actors can collaborate and work against a shared competitor, including via proxy relationships, which can create challenges in attributing any given gray zone activity to a single actor.

Gray zone challenges also depend on the perspective of the actor. As Kapusta points out, Russian activity in Ukraine may be a lower priority issue for Canada or the United States, one that might only merit economic sanctions, but it would be a top-priority issue for Russia if Western countries intervened. Miscalculation over such an issue could result in an unexpected escalation.[xxxiv]

One term sometimes associated with gray zone competition is irregular warfare. This term is defined rather broadly by the U.S.’s joint doctrine as “a violent struggle among state and nonstate actors for legitimacy and influence over the relevant populations.” But as Sandor Fabian notes, numerous “more specific conceptualizations” of the term have been advanced by scholars and practitioners alike.[xxxv] Another term associated with the gray zone is hybrid warfare, which NATO has defined as “a wide range of overt and covert military, paramilitary, and civilian measures employed in a highly integrated design.”[xxxvi] Thus, hybrid warfare can augment the deployment of conventional armies with non-conventional activities like covert operations or guerilla warfare. There is debate among scholars regarding whether hybrid warfare and gray zone competition are interchangeable terms. For David Carment and Dani Belo, hybrid warfare is a strictly tactical concept while gray zone competition represents a strategic concept. Hybrid warfare can be one form of gray zone competition, but hybrid warfare does not have to be present in an adversary’s gray zone repertoire.[xxxvii] Some, like Jean-Christophe Boucher, disagree with this characterization and argue that hybrid warfare is in fact synonymous with gray zone competition.[xxxviii]

Beyond the definitional challenges, the amorphous and ever-changing character of gray zone competition presents challenges for effectively planning for, and responding to, adversarial activities. According to one U.S. Army War College report, gray zone competition is “hard to classify, hard to conceptualize, hard to plan against, and therefore, very hard to counter.”[xxxix] For liberal democracies, the gray zone can be particularly challenging when trying to counter or compete with authoritarian states like Russia, China, and Iran, which regularly employ influence operations, manipulation, and outright intimidation that fall well short of the threshold for war to achieve strategic gain. Gray zone tactics include the exploitation of divisions and destabilizing levers within a state or a strategic ally of a state. Such exploitation aims to produce the political outcomes desired by the threat actor. For example, a rival state can focus on enabling internal resistance movements or exacerbating underlying conditions to disrupt the status quo with the aim of toppling a government.[xl]

Gray zone activities seek to alter the competitive environment such that the target does not perceive the change until it is too late. This phenomenon has been compared to the “boiling frog” fable, wherein a frog placed in boiling water would immediately jump out, while a frog placed in tepid water will not jump out as the temperature is slowly raised until it boils alive. Similarly, sudden upheavals in the international environment may prompt a swift response from world powers, but slow and barely perceptible changes can acclimate those same states to a new normal. In short, a clear and present danger will likely become a major priority to be immediately addressed, while multiple smaller nuisances are weighed amid competing priorities, allowing them to be put on the backburner until the strategic environment has dramatically changed, one barely perceptible step after another.[xli]

One example of such gray zone competition can be seen in Russia’s activities vis-a-vis Europe. The use of information operations aimed at undermining political institutions, coercive energy deals that exploit European reliance on Russia, military demonstrations along Russia’s borders, and infiltration of disputed territory all highlight how Russia uses IOs and seeks to compete in the gray zone.[xlii] Russian activities in Georgia, Crimea, and Ukraine’s Donbas region all employ political, military, and economic activities that not only fall short of the threshold of war but are hard to properly attribute to the Kremlin.[xliii] As Russia has increased its activity in Ukraine, so too did the Kremlin increase its manipulation of energy resources, subsidization of pro-Russian media, interference in the Ukrainian electoral process, and the ambiguous and disinformation-laden deployment of Russian soldiers to Crimea. These soldiers deployed wearing generic green uniforms with no identifiable markings denoting the country they belonged to, introducing plausible deniability for Russia and prompting the soldiers to be referred to as “Little Green Men.” These activities were made even more ambiguous by concerted information operations aimed at buying time for Russia to solidify its influence in the Ukraine, making information operations a critical component of gray zone competition.[xliv]

2.2 Information Operations in the Gray Zone Context

Information operations serve as a valuable tool for gray zone competition. IOs can exploit an adversary’s internal vulnerabilities, such as societal divisions or political trends, through the dissemination of propaganda or other information that compromises a target in order to acquire a competitive advantage.[xlv] While IOs are not new, the modern information environment has provided new means for IOs to be employed, such as exploiting the viral nature of social media to reach unprecedented numbers of people, enabling what some have called a “firehose of falsehoods” stemming from rapid creation of false and easily shareable material.[xlvi]

Information operations target the civilian population, making influence on a target population more relevant than ever. This notion of influencing a population is virtually timeless, as it is discussed at length in Sun Tzu’s Art of War. Thousands of years later, World War I-era general officer Giulio Douhet put forth a theory of breaking a civilian population’s morale, suggesting that the direct use of bomber aircraft against adversary populations could be a way to ensure victory on the battlefield.

Some modern IOs deployed by adversarial countries like Russia use social media propaganda, state-run news agencies, automation software, and fake online personas to amplify their chosen narratives. Russia’s actions have focused on influencing European elections, distracting attention from Russian activities, and sowing confusion. In the words of Russian General Valery Gerasimov, “long-distance, contactless actions against the enemy are becoming the main means of achieving combat and operational goals.”[xlvii] Similarly, the People’s Republic of China has used IO as a way of controlling the narrative around its Belt and Road Initiative to shape perceptions of the project as a tool of global peace rather than an effort to gain a strategic competitive advantage.[xlviii]

Information operations also enable non-state actors to conduct gray zone provocation. For example, both al-Qaeda and Daesh have conducted IOs that spread their propaganda online, attack Western cultural values, and recruit. Internet forums, social media sites, and encrypted communications platforms have all served as key parts of these IOs, allowing al-Qaeda and Daesh to spread their propaganda, celebrate attacks, and recruit or inspire new members and attackers. Such efforts reflect that gray zone competition is not limited to states. Organized non-state actors can reach larger audiences by adopting modern technologies and adapting the information operations used by states to their own purposes.[xlix]

2.3 Gray Zone Information Operation Targets

Both state and non-state actors engaged in information operations against a target aim to shape the information environment in a particular way, often to distort the perceptions of a target audience toward a certain end. For example, by making a population have a more favorable view toward the actor, by exploiting divisions between two or more groups, or by turning a population against a target state or political entity, a rival state can pursue a competitive advantage and/or achieve their end, typically a desired political outcome.[l] This can be done by amplifying narratives that align with the actors’ goals, undermining or suppressing narratives that do not align with these goals, or influencing opinion to destabilize or interfere with an adversary’s internal politics. To do this, actors rely on psychological biases inherent in the target audience, social and political structures within a society, the means by which information traverses through the information environment, and emerging technologies.

The demographic characteristics of a populace can be exploited by information operations. A U.S. Army manual on the conduct of IOs identifies factors like age, gender, education, literacy, ethnic composition, unemployment rates, and languages spoken, among others, as characteristics to be studied by IO officers. These factors impact how information transmits through the target environment and how it may be received by a target population.[li] An adversary could deploy IOs that seek to exploit these characteristics in ways that will destabilize a target.

Similarly, a state’s social structures offer means that can be exploited by IOs. These include political, religious, and cultural beliefs, affiliation, and narratives.[lii] State actors like Russia, China, Iran, and Saudi Arabia have all used divisive political topics to target divisions in the United States and Europe through “fake news” and social media bot accounts, which will be discussed in detail later.[liii]

A state’s media and information environment also shape the ways in which IOs can be conducted to reach a target audience in furtherance of an actor’s gray zone ends.[liv] Characteristics of this environment can include traditional print media, mainstream media (such as cable news channels), new and alternative media (such as newsletters or news websites), and social media. While discussed in more detail in the next section, actors can craft IOs that exploit a particular medium or multiple media formats to reach a tailored or a broad audience.

One way in which information operations are tailored to a target audience is through the creation of a strategic narrative of an antagonistic nature. Such narratives allow actors to create “a shared meaning of the past, present, and future” to influence behaviors both at home and abroad. This, for example, might entail a shared cultural tradition or origin story, like those found in religions that ground members in a shared starting point and purpose. While strategic narratives can tell a convincing story, a narrative used antagonistically can pull together a compelling story through misinformation, oversimplification, or even manipulated or intentionally falsified information that offers a distorted view of reality.[lv] Given the complex nature of the world, a compelling narrative that allows otherwise chaotic or seemingly random events to make sense in the mind of the consumer is a powerful psychological tool. This tool can be deployed by a government communicating with its population, by malicious actors like hostile states or non-state actors, or by parties attempting to influence political discourse in support of their cause or agenda.

While the media environment was once more centralized, information and communications technology (ICTs) have rapidly evolved to enable broader content creation, producing fragmentation in the dissemination of information. Actors conducting IOs have taken advantage of this to create what scholars have termed situations of implausible deniability. Where plausible deniability seeks to enable secrecy of covert action, implausible deniability seeks to sow confusion by polluting the information environment in such a way that the public can no longer determine fact from fiction. This allows a state or non-state actor to gain a competitive advantage in the gray zone while its adversary struggles to determine what is happening. As one Russian practitioner of this approach suggested, the goal of implausible deniability is “to generate a situation where it is unclear whether a state of war exists—and if it does, who is a combatant and who is not.”[lvi]

While IOs have previously sought to interfere in various countries’ internal politics, the internet allows for organic amplification of IO efforts. These technologies allow for interference in elections, inciting and mobilizing individuals to violence, and undermining the legitimacy of democratic institutions, all at a distance and at a scale that can reach millions of people with a single social media post. And newer technologies provide new ways of influencing a population. Deepfakes, artificial intelligence-produced videos, are one such method. Similarly, cheapfakes, poorly altered source material aimed at changing or implying something that is untrue, are another method of influence. While deepfakes have yet to reach the threshold of being highly impactful (though this dynamic appears to be changing rapidly), cheapfakes have already deceived audiences in ways that amplify false narratives.[lvii] Further, the very existence of these technologies enables a “liar’s dividend,” in which the existence of fake news, deepfakes, or other manipulated content can be leveraged to deny or write off documented bad behavior. A controversial remark or scandal can be denied or called into question by claiming that it is nothing more than manipulated or “fake news.”[lviii]

As awareness of the threat of IOs increases, states, companies, and non-governmental organizations have placed greater focus on understanding the issue, but the means of carrying out IOs continues to evolve rapidly. In mid-2021, Facebook shared research into threat actors’ use of the platform to carry out what the company termed “Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior” (CIB). As actors gain more experience with social media IOs, Facebook researchers noted a shift toward targeted efforts aimed at small communities. Actors are going to greater lengths to involve real people, as opposed to just falsified personas or automated accounts, in their IOs in an effort to lend an air of legitimacy to the operation. Actors are also diversifying to numerous platforms, including non-mainstream services such as Gab and Parler, to avoid detection and deplatforming efforts. Facebook researchers also noted that actors used “perception hacking,” an IO tactic that exploits concerns and fears about IO itself to sow doubt and distrust (for example, in electoral systems).[lix]Perception hacking takes advantage of the fact that when citizens no longer know what to believe, or when the amount of effort it takes to learn the truth about current events grows significantly, people disengage. Perception hacking can thus foster a sense of apathy. Voters who are primed to expect an IO targeting elections may question the validity of the election results if their candidate loses. The result is an erosion of the so-called trinity of trusts: trust in democracy, authority, and one’s fellow citizens.[lx]

3. The Gray Zone Information Context

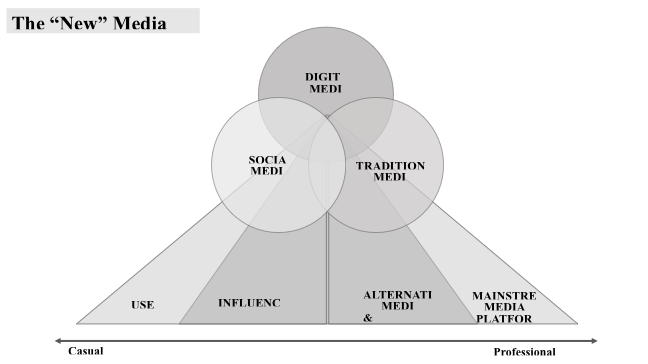

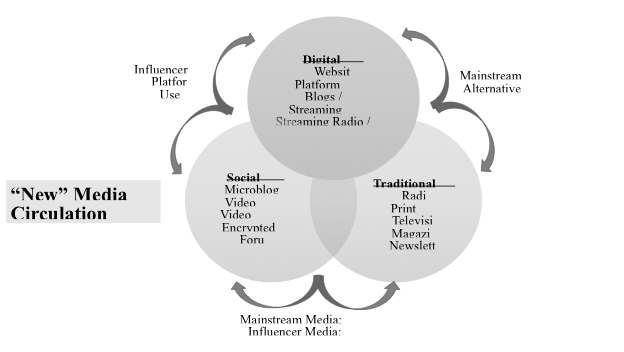

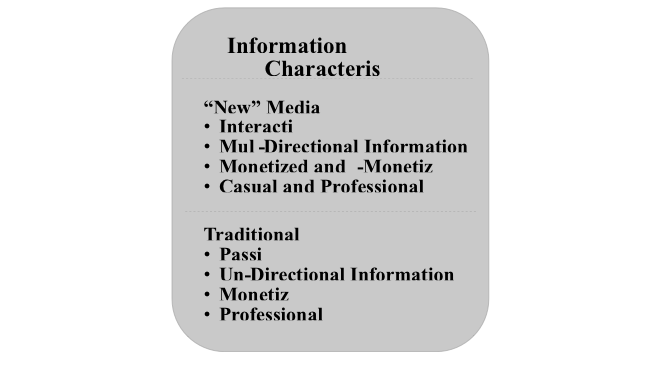

To understand the development and deployment of these gray zone IOs, it is necessary to describe the “new” media ecosystem—inclusive of technology, people, practices, and culture—within which they form and evolve. Today’s media ecosystem is composed of a set of interrelated technologies—traditional, digital, and social media—available for use by participants who may act in various capacities as sources, producers, or consumers of information, sometimes taking on all three roles.

3.1 The “New” Media Ecosystem

The contemporary media ecosystem has undergone significant shifts from prior eras when “the media” consisted of a limited set of information technologies and sources controlled by professional and governmental institutions. These shifts are predicated on the development of new information and communication technologies over the last four decades, including the development of Web 2.0 and ultimately the social web, as discussed earlier in this report. Today’s information environment vastly expands “the media” by conjoining digital media, social media, and traditional media technologies with multi-directional information sources both professional and casual, along with interactive participation on a global scale.[lxi] This shift has enabled broadened public, as well as institutional, access to participation in producing, consuming, and circulating information. It has also reduced informational guardrails rooted in professional ethics, democratic values, and factual norms. As such, this “new” media (and information) ecosystem has enabled gray zone information operations at a speed and volume previously unimaginable, and with material effects on politics, social polarization, and violence.

Today’s information environment is characterized by increasing complexity of the new media ecosystem in terms of technologies, media sources, and audiences. Its growth and development also exhibit divergent tendencies (in technological, media, and audience layers) toward both consolidation and fragmentation.[lxii] The tendency toward consolidation is most prominently seen in technological development and commercial ownership. For example, Facebook’s incorporation of Instagram, WhatsApp, and other technologies developed by smaller startups is a strategy to consolidate multiple types of services to engage a variety of user interests and ensure the company’s commercial dominance. Conversely, fragmentation can also be seen in technological development and commercial ownership. For example, Twitter-like social media platforms Gab, Parler, and Gettr formed in response to conservative beliefs about left-wing bias in moderation on mainstream social media platforms. This ongoing tension between consolidation and fragmentation has implications for shaping information flows through the practices of users, platforms, and other media and information sources.

3.2 Technological Arenas of the New Media Ecosystem

The technological arenas that comprise the new media ecosystem are traditional media, digital media, and social media. The technologies used in each arena act as delivery mechanisms for informational content, thus mediating people’s access to and uptake of information. The affordances (range of possible uses that dictate how an object should be used) of each technology shape how information is selected, stories and narratives are produced, and how the resulting products are presented. For example, the technical limitations of page width and bleed margins determine which fonts and lengths are used for textual headlines in print news, which also determines how headlines are written and edited.

Traditional media (e.g., print media, radio, televisual media, and film) each have relatively stable affordances that require specialist training in media production and access to equipment and infrastructures controlled by professional institutions. These media, often considered public media and infrastructures, are highly regulated and have strong professional standards and norms associated with their processes and practices of information production and dissemination. These standards are well known with respect to the journalistic practices of news media, but they also include the heavily regulated and professionalized standards for televisual programming, the film industry, and the radio industry. Whether audiences are interested in news, entertainment, education, or other varieties of information, they are largely passive consumers of the informational products of these traditional forms of media. The audience passivity and professionalized control associated with traditional media technologies, however, are primary features dispensed with in the technologies and forms of “new” (e.g., digital and social) media, which are designed to favor interactivity and “democratized” open access to information.

Digital media (e.g., the internet, streaming platforms, and smart, web, and cloud-based technologies) have broadly ranging affordances that remain in flux as they are dependent on continued technological development. These media, unlike traditional media, cross international borders, are used for business as well as information and entertainment, and are interconnected globally, thus posing a higher degree of regulatory complexity. They tend to be more loosely regulated by governments, and often companies’ terms of service and industry standards provide the primary regulatory structures. Digital media are considered private media, though debates over their regulation and including them in public media and infrastructure are ongoing. While digital media may require technical specialization to navigate use of affordances, particularly for infrastructural systems and coding/development, digital technologies have trended toward ease of use for average people. So, while digital media specialization may be acquired through education and traditional modes of professionalization, it is also accessible to any person who wants to learn about the technologies, coding, web development, etc., as well as through user-friendly devices and user interfaces that have enabled widespread content production and dissemination by average users (e.g., blogging, vlogging, video streaming, and podcasting). Standards for information and content sharing—particularly on web-based digital media—have developed through lay use rather than through professional or ethical standards, and thus reflect cultural norms.

Social media (platforms and apps that function to interconnect and network people according to their social connections and interests) has highly specific affordances based on platform and app design, often dictated by a preferred medium for content (image, video, music) or combinations of such media typically available through microblogging functionalities. Image-based social platforms include Flickr and Instagram, video-based platforms include YouTube and Bitchute, and music-based platforms include Pandora and Spotify. Almost all social platforms include functionality for some inclusion of text, though text-based platforms often also enable the sharing of visual media (e.g., Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter). In addition, social media have long included “anonymous” platforms like Reddit, 4chan (and 2chan, 8Chan, 8kun), and other forum-based platforms. Like digital media, social media are private media with vast global reach. Affordances in the social media environment are highly platform/app specific, adaptable, and manipulable by all users. As a particularly user-friendly sector of digital media, social media technologies are designed to be intuitive to users, as well as built and developed with content production and dissemination capability as essential features for keeping users engaged. Social media, and digital media more generally, have enabled not only broadened access to information but have also increased by vast orders of magnitude the sources of information that circulate in the media ecosystem. Social and digital media have also provided avenues to monetize user-produced content and given rise to a new sector of the media production and information industry in the form of influencer marketing, a sector that has an increasingly tangible impact on socio-political information in the new media ecosystem.

Digital and social media have generated three primary characteristics of the new media ecosystem: 1) convergence, 2) interactivity, and 3) global “public” access to vast quantities of data. These three characteristics functionally increase the complexity of the media ecosystem and information environment with definite impacts on the practice and effectiveness of gray zone information operations. The first characteristic, convergence—a term prominently employed by Henry Jenkins—is generally understood as a technological process of consolidation, bringing together disparate technologies and capabilities into single device forms.[lxiii] Media scholars, however, have argued that while convergence is easily seen in technological development, it is better understood as a cultural shift inclusive of technologies, media practices, human informational processing, and participatory engagement.[lxiv] The second characteristic, interactivity, regards a shift from generally unidirectional information flows from institutions and professional media to multidirectional information flows enabling a variety of non-institutional and non-professional sources. Interactivity not only enables, but demands, participation in the information environment and media ecosystem in ways that change our understanding of authoritative information, leading to public contention and debates about facts and truth. The last characteristic, global “public” access to vast quantities of data, is a function of the access provided by digital media, particularly the internet. However, this characteristic functions in coordination with the first two characteristics—convergence and interactivity—to shape how people consume, digest, and derive meaning from information within this new media ecosystem.

Digital and social mediation also impact the workings of traditional media (print, television, and radio). The most apparent change has been to print media, with massive decreases in circulation in journalistic print media (newspapers and magazines). Other, perhaps more subtle, changes have occurred in television media and radio, specifically in relation to digital streaming services, webcasting, podcasting, as well as blogs and video blogging (vlogs). To adapt to these changes, media companies have incorporated them into their services, running websites that house digital news in multiple formats as well as running multimodal media services across a range of platforms, from branded websites to social media and streaming services. Newer journalistic companies have also developed as “born digital” multimedia experiences. For example, Vice Media, dubbed “a poster child for new-media success” by Fortune magazine, started with a print magazine in 1994 but rapidly eschewed traditional media formats in favor of digital expansion.[lxv] The company now boasts Vice (News), Vice Studios, Refinery 29, Pulse Films, and Motherboard among its multiple brands. Other more subtle examples of the interactivity demanded of traditional media companies by digital mediation occur in relation to the development of social media norms with a particular focus on trends and virality. Now media companies source stories from social media trends and viral topics. Moreover, these stories reference details and “evidence” from social posts, in some cases creating feedback loops and in other cases spreading polluted information. For instance, Jenna Abrams was an Internet Research Agency-created account that served as a news influencer. Before Abrams’s true origin was discovered, the account “was featured in articles written by Bustle, U.S. News and World Report, USA Today, several local Fox affiliates, InfoWars, BET, Yahoo Sports, Sky News, IJR, Breitbart, The Washington Post, Mashable, New York Daily News, Quartz, Dallas News, France24, HuffPost, The Daily Caller, The Telegraph, CNN, the BBC, Gizmodo, The Independent, The Daily Dot, The Observer, Business Insider, The National Post, Refinery29, The Times of India, BuzzFeed, The Daily Mail, The New York Times, and, of course, Russia Today and Sputnik.”[lxvi] A Daily Beast profile examining the outsize impact of the Abrams account noted that “many of these stories had nothing to do with Russia—or politics at all.”[lxvii]

Audiences react and respond to media companies directly and in real time via social media and digital platforms. They share stories and expand participation in those companies’ online services, and even provide further content sourcing.

3.3 Information Sources

Along with the technological arenas of the new media ecosystem, it is essential to understand how sources of information are changing the information environment and contributing to gray zone information operations. The tension between consolidation and fragmentation, as well as the characteristics of convergence, interactivity, and global public access to vast quantities of data also impact how and where information is sourced. In prior eras, mainstream media was a primary and shared source of information for the majority of audiences. Alternative media existed—including subscription-based newsletters and magazines, as well as community and pirate radio stations—but each of these required specialized knowledge or association for access. They were also largely separated from mainstream media, with limited capacity to influence the normative information environment. In the new media ecosystem, mainstream media and alternative media remain sources of information, although their balance of interaction and capacity for influence has shifted substantially. The new media ecosystem also incorporates influencer media, platforms, and users as information sources. These sources and the information they spread now interact and inform each other in various ways that can be manipulated to the benefit of gray zone actors.

Mainstream media remains the primary source utilizing traditional media technologies and public communication infrastructures. As such, it is also the primary locus of industrial employment for media professionals (e.g., journalists, personalities, talk and radio show hosts, news presenters). The moniker “mainstream” indicates these media as being situated within and purveyors of normative—that is culturally, socially, and politically acceptable—discursive flows, even as those flows have, in the current ecosystem, developed clearly disparate strands of interpretation of information, events, and even facts. Mainstream sources have thus generally been considered reliable and fact-based information sources, particularly because they are subject to professional ethics and regulatory oversight. In the new media ecosystem, however, the mainstream media have had to adapt to the shifts brought by digital and social media technologies. Most mainstream media sources now incorporate both traditional and “new” media publication and dissemination outlets. Newspapers have incorporated digital platforms and use social media to build interest in their “products.” Similarly, televisual media and radio have incorporated websites and use social media to build online followings, but now also incorporate streaming media (e.g., video and sound clips from broadcasts, online-only streaming content, as well as podcasts and streaming radio shows). Moreover, mainstream media sources have turned to social media trends and viral content to source their own stories and news.[lxviii] In addition, if the uptake of digital and social media as technologies and information gathering sites presents a form of fragmentation among mainstream media sources by pluralizing modes of access and engagement, consolidation is at play often through the consolidation of specific channels by media corporations. In this process, competition among media corporations is reduced as a limited number of large companies buy up smaller entities and channels (e.g., radio or local television stations or newspaper publications). Consolidation here provides a mechanism for potential control over messaging and story selection through these channels. In the context of political polarization, both fragmentation and consolidation in mainstream media can work to further delineate and strengthen disparate strands of interpretation and socio-political disagreement over facts and events, essentially reifying consensus within disparate strands while disrupting consensus between them.

Along with mainstream media’s uptake of and interactivity with digital and social media, under the new media ecosystem it has also become more imbricated with alternative media. “Alternative” is a category judged against the normative “mainstream,” and as such may change over time and in relation to sociopolitical and cultural shifts. For example, under the Trump presidency, multiple previously “alternative” media sources and channels were elevated to “mainstream” status, at least nominally, because the Trump administration categorized them as preferred media.[lxix] Alternative media may include professionally trained media personalities and workers, but it also includes “citizen journalists” and other informally or untrained sources, it is less heavily regulated (if at all), and it is not subject to professional ethics. Unlike mainstream media, alternative media sources include extremist, activist, and other politically motivated information sources that increasingly position themselves as “telling real truths” that the mainstream media ignores or covers up. Alternative media sources have made ample use of the new media ecosystem’s technologies, and have often been early adopters of new information and communication technologies.[lxx] Early adoption, lack of regulation, and different organizational (or individual) goals have enabled alternative media sources to become agile in testing information strategies and tactics in relation to new media ecosystem technological developments.[lxxi] Importantly, alternative media have been able to take on and participate in shaping the cultural ethos of digital and social media in ways that mainstream media have not due to ethical, professional, and economic considerations. This has led to a twinned development of industrial, corporatized alternative media (e.g., Vice Media, Mother Jones, One America News Network, Newsmax) alongside seemingly “grassroots” influencer alternative media (e.g, InfoWars, Joe Rogan Experience, Drudge Report, Young Turks).

Influencer media sources are a mainstay in the new media ecosystem. These sources highlight how digital and social media blend sales (advertising) with news (information) to persuade followers (audiences) through affectively charged forms of persuasion. The influencer business model formed after the shift to Web 2.0 technology, which made web development easier for average users. As blogging took off in the mid-2000s, companies realized that bloggers had begun amassing large, loyal readerships, and that those followings could be tapped as consumer markets through a digitized form of “word-of-mouth” advertising, including blogger reviews of their products. This enabled bloggers to monetize their output and incentivized them to build their own brands. Importantly, influencer marketing and later influencer social media as communicative forms trade on their capacity to build a sense of authenticity and trustworthiness in their follower-bases. This type of marketing relies on relational communicative frames that mobilize heuristic persuasion—or the promotion of reduced elaboration (critical thinking) in favor of emotional response to make choices—rooted in the audience’s affinity for and trust in the influencer. The higher level of affinity influencers have with their audience, the more likely followers are to see information that influencer shares as trustworthy, valuable, and meaningful.[lxxii] Affective (emotion-based) reasoning has come to characterize online information-sharing cultural norms, helping to enable intensified information consumption practices like virality.[lxxiii] As social media developed, the influencer model has become increasingly ubiquitous, taking on a variety of forms based on the specific features (affordances) and cultures of popular platforms, shifting with platform audiences, and developing into a model in which influencers integrate their use of multiple platforms, known as 360 degree lifestyle branding.[lxxiv] Influencers are curators of taste, culture, and information. They help reduce the “noise” of the digital space and provide their followers with easy access to preferred content, brands, and important news.